.JPG) |

| Apis Cerana at work |

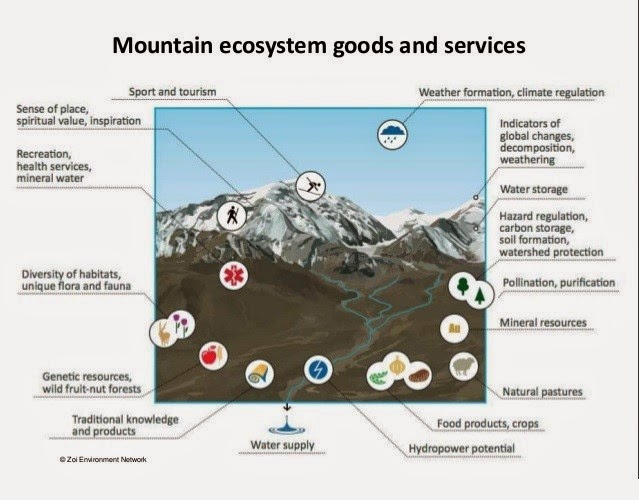

Bees play an important role in any environment as plant pollinators. Within the Ghandruk area (2000-3000 m) the indigenous honeybees of the Himalayas are essential for the maintenance of the region's biodiversity and natural ecosystems. These hard working little friends occupy a key role in the pollination of mountain crops and consequently, contribute to food security and livelihoods of the Ghandruk rural households.

|

| Don't get fooled by the Syrphid, this fly is not a bee! |

Regardless their fame, many threats contribute to the dissemination of the domestic honeybees around the world. Although one might think that "mountain bees" would be spared from these potential threats, a similar increase in colony mortality is already observed and now monitored within the ACA region.

Among these threats we observe a slow but steady shift towards monoculture practices. Limiting agriculture to one crop type contributes to loss of floral diversity (and Biodiversity) and is often responsible to increased use of pesticides. In addition to this major threat, increasing access to remote areas by trekkers, sadly, too often goes hand in hand with environmental degradation.

Here in Ghandruk, beekeeping is an integral part of the history of the rural development of the communities by improving food productivity and providing honey, wax and other products for home use and sale. This is particularly true for landless individuals who rely on trading and monetary exchanges to obtain basic necessities.

Ghandruk communities have been in the past and are even today relying on both honey hunting of the Himalayan wild bee's colonies to obtain honey and using log hives to produce honey by domestic or wild bees.

There are four groups of bees in Nepal:

- bumble bees

- sting-less bees

- solitary bees

- honeybees

According to Bahadur Gurung & al. (2012), five species of HONEYBEES are found in the Himalayas:

Little honeybee (Apis florea)

Giant honeybee (Apis dorsata)

Himalyan cliff bee (Apis laboriosa)

Asian / Indigenous hive bee (Apis cerana)

The Little honeybee (Apis florea) can be found in hills and plains at altitudes up to 1,200 m. These bees build single small comb nests under small tree branches or bushes. A colony can produce 1 kg of honey per year.

Their big sister, the Giant honeybee (Apis dorsata) is also fund in hills and plains but at lower altitudes up to 1,000 m. They usually build single large comb nests on the top of tall trees, buildings, or water towers. These big sisters are highly defensive and performs mass attacks. They also produce considerably more honey per year (30-50 kg per colony).

Similar to his cousin Apis dorsata, the Himalayan cliff bee (Apis laboriosa) is darker and more defensive. Not only they build larger single comb nests but also produce considerable more honey per year with an average of 60 kg per colony and prefers nesting on large steep rocky cliff faces.

.JPG) |

| One of many comb nests found within Ghandruk |

The honey produced by the Himalayan cliff bee is highly prized and in Nepal, honey hunting is a vital part of the Nepali culture. However, health of these bee's populations are threatened by human disturbances and resulting habitats degradation.

Finally, while walking around Ghandruk, one can find tree logs hanging on the side of houses. When the sun shine and temperature rises, all these little workers get down to work. Apis cerana (Asian or indigenous hive bee) is the only bee that can be kept in these hand crafted log hives.

|

| Log hive found on the neighbour's house wall |

They differentiate themselves from their cousins by building multiple parallel combs (number depends on the colony size) and by establishing themselves in plains and hills from below 300 m up to 3,400 m.These bees can produce up to 20 kg of honey per hive per year and are resistant to diseases and mites, main culprit of the European honeybee populations dissemination worldwide.

In Ghandruk, the European honeybee (Apis mellifera) was introduced for commercial beekeeping as it builds multiple parallel combs and can be keep in movable frame hives.

Bahadur Gurung, Uma Partap, Nabin CID Shrestha, Harish K Sharma, Nurul Islam, Nar Bahadur Tamang, 2012. Beekeeping Training for Farmers in the Himalaya. Resource Manual for Trainers International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Katmandu. 190 p.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)